Bosque

Bunni held my head, and I could taste every part of her in my mouth. Every single inch of her that my tongue wet—every single inch—sat flavorful. Her tongue soaked down to my jaw. Her hands traveled down my stomach, teased the top of my pants, and I had to stop her before I was no longer able.

“There’s not much time,” I whispered, trying not to hear my own wheezing. She nodded, her lips rubbing against my neck.

“Tell me about us, Bosque. Don’t leave anything out. I want you to tell me how you see me. I want you to make us legends.”

We stared up at the sky, and I only noticed the colors draining a little. The sounds from my chest covered everything.

“Help me tell you.”

She nodded with her lips parted, and her teeth sunk softly into the bottom of my jaw. Bunni was always biting me, always scraping me, always getting lost in whatever part of me she wanted at the moment.

What would she get lost in when I was gone?

“You try first, and I’ll pick up the slack, nature boy.”

Part 1: Before

Nothing matters but the journey, but I can’t think about anything but the end.

The end sits in my lungs, maybe growing already, maybe not quite ready to bud. I let the lives my family managed to squeeze out in the little time they had sit inside me when they felt the need, reminders that there was more to this story than just me. Before I ever existed, stories of my family lived and bloomed in the places I tread now. I’ll die young, and I’ll die in agony, but the only part that matters is the journey.

“Ignore the start, enjoy the middle, embrace the ending.” That’s what my grandmother used to say. Before she changed her mind.

Coughing in a field while I search for food, waiting to see blood on my hands someday, I sometimes think about the journey I’m avoiding. The worst part of this disease is the way it makes you remember. While you feel your lungs fill with mucus and dirt, feel your horns turn to soft wood, struggle to breathe through the fluid, you think about all the other times you’ve heard that gurgle.

Is it louder than the last one? Thicker? Does it shake the same?

When you have the disease, you think. You think about the different ways it sounded in each of your family members. Maybe a death rattle is a fingerprint for the sick. My mother’s had a slight lilt. It was pretty, like flowers bloomed in her lungs and pushed the sound out. My father’s had a gruff to it, a bit of baritone. My little brothers and sisters all sounded like birds. Wet chirping, night and day.

I sit around and think about noises, even when the rain drowns them out in my head. It’s a rainy country, at least the part I’m banished to, the part that my family owns. My family’s land is barely ever dry. The animals like it, and I’m keen to do what the animals do.

And every now and then, I wake up and want to live.

It’s usually the hunger that does it. You can only ignore the desire and need to eat for so long. It always feels like an interruption, though. Who wants to recount stories of meals alone, of sitting around stuffing leaves into your face? My ribs were getting more and more friendly with the outside world, my skin stretched tight between them, but I didn’t leave my concrete home. When there was no more food in the fields, I went home and sat around all day. I pulled on my stomach to pass the time, staring out the window at the barely visible sun. Somewhere, maybe, it was blinding. Somewhere, it was sinking into someone’s skin, bathing them, filling them with hope.

The ceiling waved in my vision, but it was only a little. It’d been worse.

My bed was a lot of dried grass, a lot of leaves, and some actual cloth my mother had sewn for me. There was a bunch of it in her garden, piles of cloth dirtying with time. I hadn’t touched any of it in years, and maybe I’d do better if I at least brought the supplies out. I wasn’t supposed to get sad about death, immobile even. Definitely wasn’t supposed to get so sad that I sat in the rain all day. It was hard to do what my mother and grandmother said now that they were gone.

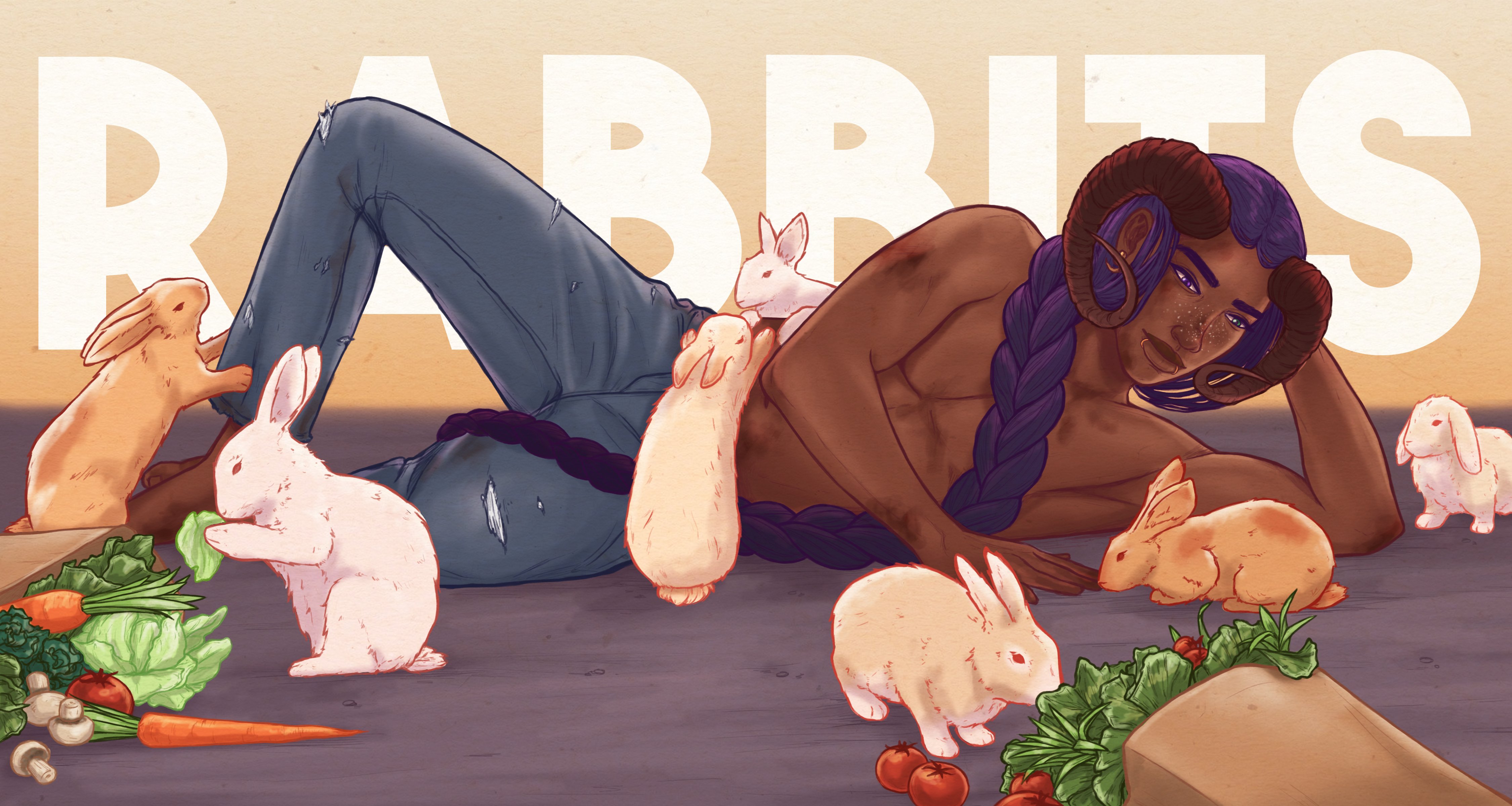

Time passed, and I knew it passed because of the rabbits. The sky opened up a bit. I sat on the ground in front of my bed, feeling myself sinking. I pulled at my stomach again, watching more and more rabbits jump through the doorway, and drooped even more. I’d stopped naming them when my grandmother died, when I found them covering her, nudging at her stiff body. I didn’t hate them; I just didn’t name them anymore.

“Don’t bother me,” I muttered, but they ignored the request.

They nibbled at the leaves growing from the cracks in the windows. Before I could stop myself, I crawled over, hands nearly numb, and plucked a piece of something green from one of the rabbits. I couldn’t bring myself to put it in my mouth. It took it back, wriggling it, then leaned up to offer it to me. It watched me take a bite and patiently took it back when I gagged.

The other rabbits jumped around, nibbling and watching, and it felt like the concrete walls were crawling toward me, the floor crunching under me. I wondered what all of it tasted like. Could I fit all the rabbits in my mouth? Did the floor have any fruit left on it, trampled flat by the many human and animal feet over the years? The rabbit stopped chewing when I got closer and pushed my nose against it, but I pulled back.

Grandmother loved them, so I wouldn’t eat a single one.

“Can’t be helped,” I mumbled to the rabbit. Its nose wriggled.

It was time to go shopping. Three months of fruits and vegetables from the forest isn’t enough to survive for Horns. Being sick helps a little. I find myself able to eat depression instead of meals often. But it still isn’t enough.

We’re mostly carnivorous, by choice and by design. It’s something my grandmother complained about often. Maybe she would have lived longer if it wasn’t for her aversion to eating animals. That thought is one of the few things that can send me to the city to shop for food. I absorb her desire to live the older I get, whether I try to ignore it or not.

“Can’t be helped,” I mumbled, staring down at the rabbit. It stared back in understanding, I think. “Unless I’m eating you?”

It jumped away, and for a second, I wondered if it understood me, but who knows? Who knows what they know?

I packed my large canvas bag and tied a scarf around each horn, my annoyed grumbles louder than my growling stomach. It took a while to cover them adequately, and even then, staring at my reflection in the dirty mirror, I realized I would probably turn more heads than avoid them. But I couldn’t be bothered to change my headwraps.

These savages would look no matter what I did.

There’s nothing worse than Horns.

You get a taste of the viciousness of my people the minute you step into any highly populated area. Someone’s arguing. Someone’s sneering. Someone’s kid is screaming or laughing too loud. It’s always just an abundance of noise and testosterone. The only way I manage it is by thinking of the forest, trying to replace the screaming or arguing with chirping, the sounds of rain, of insects. I remove the aggression and imagine the river by my house, bears growling, rabbits wiggling their noses. I understand a lot why nature cannot exist in the city.

Horns are nothing but chaos. I want my last years to be as devoid of their noise as possible. I check my breathing before I walk into the supermarket every time, listening for mucus. This time was no different. I took a deep breath, concentrating.

There’s nothing yet, Bosque. Relax.

I’m not afraid of it. I just like to check.

Inside, avoiding the stares of women Horns out to do their weekly shopping, I stopped by the meat. As much as it brings me shame, I’m a fan of rabbit meat, sometimes venison as well. I stay away from veal or eggs or anything that didn’t get a chance to live.

I picked over a tightly wrapped shank, wondering what I could cook the quickest. How much could I carry back? A ravenous feeling took over me, and I fought the urge to eat it all, every leg, every shoulder, every single mutilated part.

Is the butcher open?

The pre-cut selection was fine. I didn’t want to put myself in a direct conversation, having to stare down the lone Gore Horn at the meat counter and answer questions about the type of meat I was buying. She glanced at me, eyes gaunt and tired, and I nodded. She didn’t return it. I adjusted my headwraps, deep in my nerves, adding two prepackaged shanks and a shoulder to my basket. They’d fit in my bag.

Maybe some fruit, though it would be a waste to buy too much.

There was a sudden sensation behind me, tingling along my shoulders. I jerked forward. A woman walked close to me, really close, and let her hand trail my back as she passed. She nicked my shoulder with a long nail. I could feel her breath and wondered how any girl could be as tall as me. I didn’t have much experience, but I’d always been taller than the healthy horned girls, though not most of the healthy horned men. My sisters were naturally long; my mother was lean and high up, my grandmother the same. Wood Horns just grew more. I always figured healthier women were smaller, sometimes even tiny.

I ignored the touch.

I found a section of spices and pondered over them.

An argument I couldn’t block out with bird chirps invaded the quiet of the shop. We were nearly alone in the store: me, the tall woman, and the men surrounding her. I couldn’t feel any eyes on me anymore. It had a lot to do with the men; nothing clears out a store faster than angry Boars. The base of my horns tingled, and I tried to shop faster. I didn’t feel like dealing with them, not with my stomach creeping toward my spine.

There was a whimper, and I turned without meaning to.

She was the longest woman I’d ever seen out in public. Comically, she had a pair of pink heart glasses pulled up over her eyebrows. The woman pleaded with me silently, her face still. I looked back at the spices. The Boars were bigger than I’d expected, too close to her to be friendly.

My stomach growled.

“Go ahead out the door, Bunni. Don’t make me drag you out of another place.”

There were three men, all enormous, all with thick, impressive horns. They weren’t Primes, but they were a different breed of Boar, all too thick to be normal. The woman had on a deep, dark shade of purple lipstick that almost stopped me from turning back around, her lips full and moist. Her hair trailed gently down her back, past her thighs, stopping only a few inches from the floor. Every inch of her legs were exposed, right up to the tiny shorts that could’ve been underwear. There was a bright pink bag next to her foot, and she rocked against it.

I lost myself in studying her. Corset piercings on the outer side of each leg traveled up until they reached her tiny shorts. Maybe they went higher; I couldn’t tell. They were pulled tight with pink ribbons. My eyes traveled her thin frame until I met hers, still defiant with that tiny plea. There was a puffy hat over her head, hiding her horns, but they poked out a tiny bit on the sides. They were flat.

Flat means Tivah. Just get your meat. Don’t bother them. You know the rules.

I heard them moving with little struggle. When I looked back up, they were gone, the woman’s bright pink bag left behind on the ground.

Slow, I took my meat to the checkout girl and handed it to her. I’d settled on four spices that would last a long enough time to make the vegetables bearable, four different selections of rabbit, a long slab of pork, and a small variety of fruits I couldn’t find in the forest. The checkout girl eyed me warily, her thin antlers prominent and dainty, rising charismatically from the top of her head. I didn’t pretend to care.

“Is that all?” she asked curtly.

I nodded, handing her a wad of rolled-up bills.

“Seriously? You don’t have a card?”

“No.”

Her thick scoff managed to be amused and irritated at the same time. She unrolled the bills, shaking the dirt out of them, disgusted.

“Please tell me I can just keep the change …”

“No.”

Huffing, she opened the register and counted out my change, sliding the dirty bills in reluctantly. I nodded, grabbing my tote bags of food, and headed back to the pink bag.

Just leave it alone ...

But I couldn’t. I couldn’t leave the bag there, and I couldn’t open it. And I couldn’t stop thinking about those piercings, pink lace connecting each loop, or the flat horns. Those nearly enormous lips, so full they looked like they’d vibrate when she spoke. I couldn’t stop thinking about her staring at me, waiting for me to help.

My mother, dead and gone and sick all her life, would have died again if she knew I’d let them take her, if she knew I allowed a bunch of thugs to drag a woman out of a store, that I stood there and watched.

I grabbed the bag and headed out the back door, hungry and irritated.

One of the last conversations I had with my mother helps me navigate manhood more than any single presence in my past.

“Bosque. It’s my turn.”

My mother’s name was Mayan, and she had a tattoo on her chest with the name in small block letters. It sat right where her throat began, the red lettering elegant on her skin. She liked pretty things, beautiful things. There were roses all over her hair, the thorns messily tearing into the skin around her forehead. She’d constantly bleed, only allowing my father to wipe her skull.

This conversation was right after my father’s death, after his public execution, the one that drew hundreds of Horns. The public execution and humiliation that ensured my family's historical status, the one that gave me the right to kill.

My mother was so close to death that my small siblings had to walk with her to get me. All of them sick, all counting on me to take care of them. Her body was so thin, and her grief so enormous, so engulfing. I can feel that grief everywhere at even a passing thought of her. Even the degenerates that make up our country felt pity for her. My mother had too much pride to accept their help, but sometimes we’d receive a food ration that she didn’t turn away. With my father gone, she couldn’t afford to ignore peace offerings.

There was a bouquet on the table with a small card.

Sorry for your loss, Mayan.

“This is from town. They neglected to send your father’s body with it.”

Slow. Every movement I’d ever seen my mother make was slow and deliberate. She handed me a wet rag and pointed to her bleeding head.

“Please.”

“Of course, Mother.”

I wiped at her wounds, wincing at how deep they were. We could hear my grandmother wailing in the woods, howling in grief. I tried my best to remain calm, bare-chested, the sudden man of the family.

“You’re so healthy,” she marveled, running her fingers through my hair. I let it fall down my back, silk straight.

“I’m trying, ma’am. I’m not afraid, though.”

“They’ve killed me, Bosque. They’ve killed your grandmother. You’ll be the only one left soon.”

“What about the kids—"

“You can hear it in their words. Gurgles. Moisture. They’ve already started. You’ll be the only one left.”

She gave me a kind, encouraging face. It didn’t calm me.

“We were only protecting ourselves, Mother. They hurt Dahlia …”

“Yes. They always hurt us, and they always will, my little tree. Your father should’ve known better. We’re all going to die anyway. Now, I’ll die without him. That’s a choice that he made, and he made it loudly and without thought.”

I brushed her hair until she lifted painfully, kissing my hand in thanks. The blood stained her face in dark streaks, barely lifting when I wiped.

“There is beauty in solitude, Bosque. It’s a crushing, noisy beauty, and you have to accept it to live. You are the last of us. Don’t let anyone take you, and don’t take yourself. Do you understand? The wood will take you when it’s time.”

“Yes, ma’am. I promise.”

She nodded, and my siblings appeared out of nowhere to cart her away. They sounded like a car engine, the rev of their lungs, the pressure in their steps.

She was gone so soon after that, I didn’t get a chance to argue.

The meat I purchased needed to be salted. I’d stuffed most of my items in my big backpack, slinging it over my shoulders. The little pink bag glistened as I stepped out the back door. The Boars had the woman cornered, so close to the door that I hit one. We were in a tight walkway on the side of the building. It was big enough to let delivery carts through, nothing more.

“Watch yourself,” one muttered, rubbing the shoulder I’d hit.

The woman’s shirt was ripped down the middle, and one of the Boars had his hand pressed against her chest. She covered herself uncomfortably.

“What did I say?” the Boar touching her asked.

She huffed. “My father didn’t send you out here to assault me, Oroh. He’d never let me have that much fun.”

Her words were too wobbly to be mocking. She noticed me in the door, and a small noise left her throat that reminded me of the rabbits.

“Hey,” I tried.

They ignored me, Oroh moving close enough to her that I couldn’t see anything but her legs. He pressed against her, laughing.

“Your father doesn’t know you’re out here ruining the family name again, does he?”

“By shopping?”

“More like selling drugs. Fucking for money. Whatever it is you do when no one’s watching.”

“Excuse me.”

I pushed the door harder against the Boar, and he finally turned, his face screwed up. They all shifted a little, but the big one stayed focused on the woman. I sighed, pulling my scarves off of my horns. They stood in silence for a moment, taking in the thick wood curving down from my head.

“Shit. Hey, he’s a Wood Horn. They’re contagious, right?”

The smallest one stared at me in fear, covering his mouth and nose.

“No, you idiot. Hit him. They’re like a pile of twigs. He’s probably halfway dead alrea—”

I grabbed Oroh by his thick, black shoulder horns and slammed him down. The two lackeys backed up a little, nervous.

“You’re one of the Nameless ones, aren’t you?” Oroh asked, not nearly winded enough for my liking.

“Who knows?”

“Easy enough to tell. You got a name?”

“Bosque.”

They waited, all staring in suspense. The woman stared, too, pulling her shirt tight around her.

I pressed my foot into his chest and let myself enjoy his pause. Was I nameless? Was I a plain old dying Wood Horn, or was I really a Nameless Historical Wood?

“No last name. Just Bosque.”

The two smaller Boars groaned at the same time. The one on the ground stared up at me, curious.

“You’re the last one? So if I get rid of you, we don’t have to worry about the prison sentence, right? Who would tell?”

My stomach grumbled in response. The woman sighed.

“Look, you’re already feeling up a Prima, now you want to fuck with a Nameless? Are you that desperate for an execution?”

The guy grunted and lifted me off of him easily. I kept my hands in my pockets, trying to look tough through another stomach grumble. Oroh cracked his neck as he stood up, humongous, and I wanted badly to erase him from the planet.

“All this noise over a little rich aristocrat. You Woods really are pathetic for women.”

More rage bubbled through me. I had trouble hearing beyond it, but the woman licked her purple lips and pulled her shirt all the way open. She reached in her pink bag for another.

Her breasts were perfect. I blushed, turning to stare down at the ground. Oroh laughed, whistling.

“Looks like I have a Wood to protect me now. Guess you’d better keep your hands to yourself.” The Boar turned, winking at me.

“We’ll see about that. Enjoy your little Prima while you can, dirt mound.”

Part of me felt like I’d made a mistake. The words stuck to me, their intentions going well beyond a fight in an alley. He’d be back, and he’d be back for her, then he’d be back with more for me. There was no point in coming back if he wasn’t going to kill me. Not when I was legally allowed to kill him.

They walked off, the small one smashing his fist into any solid object he could find on the way up the street. We both waited, holding our breath. When they were finally out of eyesight, the woman turned to me, letting her eyes stop on every part of my body.

“Bosque, you said? No last name?”

“Yeah. Sorry, I didn’t catch your—”

She dropped down to her knees, and I barely had time to move back before she’d pulled my sweatpants down. Her lips pressed against my navel, then she took small bites down to my pelvis. Her long nails slid between my fingers when I tried to stop her, and she pushed my hands behind my back.

“Hey! Hold on! You don’t have to do that—”

“It’s my pleasure, Bosque. And I’m Bunni, with an i.”

I tried to stop her again, moving along the wall, but she followed me, a smile gulping up most of her face. The walkway was dark, but it was still broad daylight outside. People walked by on either side of the building, oblivious.

Bunni ran her nails back around my stomach, laughing when I gasped.

“You’re sensitive! Such a strong man, gasping like a scared animal.”

She kissed either side of my pelvis, and I grabbed the back of her head instinctively.

“Oh! What do you want me to do?”

“Nothing. Nothing, I’m sorry.”

She pulled my dick to her mouth and waited.

“So I shouldn’t?”

Maybe it was my imagination, but I could see my heartbeat throbbing through my stomach. Bunni ran her hand up to my chest, moving me closer to her mouth. She let her tongue slide along the underside, from my tip to the base, and I gripped her shoulders harder. She laughed. It vibrated through me, sending me back up. When she finally put me in her mouth, she moved all the way down, and the tightness of the back of her throat made my eyes roll.

It wasn’t my first time doing something sexual, but it was my first time experiencing oral sex, and I reacted accordingly. Bunni reached up with a long arm and wrapped her hand around the base of my throat, cutting off my moans. I worried I would hurt her, but I couldn’t stop my hands from digging into her shoulders harder. She moaned, moving her lips back and forth over me slowly.

Redness crept up my stomach like a fuse, and by the time it reached her hand on my neck, I was holding onto her for dear life. She pulled me out of her mouth and let go of my throat, still holding me with one hand.

“Cum, nature boy.”

I don’t know why. It’s not like I never take care of myself or have never felt any sexual stimulation, but when she said cum and looked up at me like she did as her tongue stretched down the entire length of me, I did. I grabbed both of her shoulders, sucked in a painful breath, and I came.

My father never introduced me to my first girlfriend. He was supposed to. We were supposed to go to the city and meet a Wood Horn, one that abandoned the forest. The woman wanted to fit in with a healthy society, but she also wanted to carry on our traditions.

“Idiot beast,” my grandmother hissed. “Hiding herself! Out there living in the city with those savages! I don’t want my Bosque with her ungrateful city children—”

“Your Bosque is going to die alone,” my mother said, turning in her seat to meet my grandmother’s eyes.

They had an odd relationship. My grandmother never yelled at her, she never cursed her, but she never openly loved her, either. My mother was slight, thin, and frail. My grandmother was larger, her age bending her, with leathery, sunburnt skin.

“My Bosque will live. You don’t have to believe it. But he doesn’t need to live with those savages taunting him. How does she stand it out there? What type of children could she have if she’s ashamed of her people?”

My mother listened to my grandmother respectfully, never mocking her. I watched them all, my hands clasped behind my back. They always gathered around my mother in her little garden to talk.

All I could think about was meeting a girl, getting to meet a girl that wasn’t in my family, a girl that wasn’t working with the other Woods on the sides of the roads into town.

“He has to go,” my father sighed, and my mother showed her gratitude by handing him a rag to wipe her forehead. He did.

My grandmother huffed over to me.

“Don’t let the city beast take your pride! Don’t let them leave you there. You come back to Granny and the rabbits, understand?”

I nodded, and I meant it. I’d bring the girl back if I had to, but I wouldn’t leave my grandmother.

My mother thought for a moment, then turned to my father.

“He will come back, won’t he?”

“Of course. I’d never leave him with those scum. She’ll let the girl go, or he can go back for her if she survives to adulthood.”

My mother nodded, appeased, and gave me a heavy smile. She sucked in a deep rattle of breath.

“Be sweet to her. Women enjoy sweetness sometimes.”

“She’s a city girl. Hit her with a rock. Girls like aggressive boys,” my grandmother said, her voice trailing off behind me.

My mother let out a prolonged cough, trying not to laugh.

I should’ve known I wouldn’t meet the daughter. The way my family cursed their entire existence, the way my father walked around in sour anger, I should’ve known. He packed up logs for protection, finding thick ones that could do damage.

“The city people aren’t friendly,” he muttered when he saw me watching. But the idea of it excited me. Even the concept of the city excited me.

We left at daybreak, my father tugging a small tote filled with logs. I couldn’t lift the logs. I was very young, and they weren’t sure if I was going to die yet. Wood Horns pair off sometimes, especially if one presents as healthy. It makes sense to keep the bloodline going with a healthier Horn. You won’t find a Prima or even a regular Horn willing to mate with one of us, so we can only count on “healthy-presenting” Woods. I was almost in the double digits and hadn’t had a single cough, so I was the closest to healthy my family had to offer.

I can’t remember her name. I only remember the way my heart beat when we reached the city, emerging along a dirt road that suddenly turned to asphalt. I remember the way people turned to stare at us. I remember how clean they were, how solid their horns were, how my father’s face grew tighter and tighter as we walked. The way the mocking started almost as soon as the Boars showed up. The way children approached us, then laughed and ran off. The way the people circled us dangerously. The way my father gripped one of the logs in warning. We were myths. I thought that maybe these people hadn’t adopted language, that they only understood whispers and laughter.

My father led me through the city, and when we got to the large building, we stopped. It was the fanciest place I’d ever seen, with the first elevator and glass doors I’d ever stood near. The doorman wouldn’t let us go up. The Wood Horn had to come down. She was as clean as the others, a tight fabric covering her legs. I was in awe until my eyes reached the top of her head, seeing her short hair. Her horns were thin, spiraling to either side of her, and beautiful. But they were white. Wood Horns don’t have all-white horns. The infection turns them brown. We all have at least one brown horn.

She started to speak, smiling down at me, but my father scoffed.

“You’re not a Wood Horn.”

The woman looked surprised, then offended.

“Excuse me? They’re painted. Of course I’m a—”

“You painted your horns?”

“I had to. For my job—”

My father laughed, doubling over from the effort.

“Does that work? Is the wood gone?” he asked, tears in his eyes.

I felt my body stiffen, blood rushing to my face, and I did my best to look sorry. The longer he laughed, the more mortified she looked.

She blushed and went back upstairs. We left without being kicked out. All the way back to the forest, seething, I wanted to ask him why he’d ruined my chance, but he never said anything. When we got home, he wet a rag and wiped my mother’s blood away. They both laughed at the stupid woman from the city.

“Go get the rabbits for dinner,” my mother smiled to me, and you could hear my grandmother complaining about it from the top floor of the concrete house.

I did what I was told, sobbing silently all through the task. The little ones watched me, but none of them asked what was wrong.

I’d never actually gotten to meet any girls while my family was alive. It wasn’t a concern after that day. There was no point in me meeting anyone, not for long-term purposes. I think they all knew the time of the Nameless was coming to an end. The woman in the city painting her horns, trying to hide the wood, she was a Nameless as well, and she died a few years later.

That’s what they were becoming: ashamed legends that did their best to fit back into society before it was time to go. My family would rather die out than assimilate.

Bunni wiped her mouth on her shirt, spilling my cum out in waves, giving me a look that tested my strength. She took her shirt off and stuffed it in the pink bag. I watched her pull out another shirt, wondering why she kept so many.

“How sexy! Who taught you to cum on command?”

She was still kneeling, gripping my sides. I tried to pull away, but she followed, chaos in her eyes.

“I think that’s good enough as a th—thanks, miss …”

“Bunni.”

“What?”

Her smirk pushed against my pelvis, and she finally pulled back a little.

“Bunni’s my name. I told you already, so you should use it. I like the way you talk. What’s that accent? Are these wood horns? Are you actually Nameless?”

She licked the tip of me, just a little, but I jerked forward and moaned. I tried my best to push her back gently.

“Bunni, I’m glad you’re appreciative. I’m going to go.”

She squeezed her fingers, rolling in slow circles.

“Just wait until I’m done thanking you.”

I finally pushed her back as hard as I could, ashamed at her stunned expression. She sat, stunned the entire time I covered myself.

“I’m sorry. I’m glad you’re OK.”

I grabbed my bags off the ground, leaving the scarves behind. The feeling of her watching me followed me to the edge of town. The sensation of her touching me, her forcefulness, lasted the entire way back to the concrete home.

I salted the meat, and I thought about her. I washed all the pots I had in the river, and I thought about her. Even with the lust-filled memories she’d given me, I thought about her name.

Bunni. What were the odds?

Her horns were poking out from the hat, flat against her head. I wanted to see them. I tried to understand why her mother looked down and named her Bunni when she was born. What significance was there in her name, in her small, scared squeaks?

My grandmother meant the universe to me. I thought about her a lot, even years after her death. I thought about her more than my siblings and my parents. Her obsession with those rabbits left me starving in the woods so often. The rabbits greeted me every morning, following me everywhere. And here was a woman named Bunni.

My grandmother always said I would live. She would take the dirt from my lungs from wherever death took her. As I washed my horns, checking them for mold in the mirror, I thought about that.

Wherever I go, I will grant you life.

My big concrete home was filled with rabbits that night. I’d never seen so many on a rainy day. It’s a sign, I thought, too hopeful to feel silly. It’s a sign from Grandmother.

Those same rabbits swarmed my grandmother when she died, crawling over her face, her stomach, her clenched fingers. They either mocked her or stayed with her, keeping her comfortable until she passed. Depending on the day, I saw it as one or the other.

They watched me while I wandered through the fields to find vegetables to go with my dinner. They watched me when I sat in the forest, letting yet another rainfall drench me, smelling the moss and the still water. I hadn’t felt so empty, so relaxed, in my entire life.

Bunni. The rabbits all seemed to follow me, to wonder where I’d been, why I was so shaky. I sat back in my spot in front of my bed, staring out the window at the city.

I’d never believed in signs before, but as the soft rain turned into thunder and a sobbing sky, the rabbits came. They filled the building. I went to sleep with the smell of wet fur and the soft scrapes of rabbit feet against the floor.

I’d go look for her the next day.